Simply Feeding Horses

by Diederick Labuschagne

This is by no means intended to be a scientific paper. However, it would seem that there are as many opinions about feeding horses as there are owners, trainers, breeders and riders. That the “art” of feeding horses is often tips and tricks that is passed on from generation to generation. These may be facts or myths, but is believed as gospel by those who practice it. In this article I will endeavour to address the topic based on scientific facts, yet still being practical about it so that it applies to the day-to-day feeding and management of feeding programs.

It all started about 55 million years ago when a small “dog like” animal called Eohippus (dawn horse) emerged from the forests of the North American continent to roam on the grass planes of the world. Here they evolved to the modern horse, Equus caballus, a majestic animal of high intelligence and a superb athlete. The evolution process was a complex one going through many phases but for our purpose it will suffice to highlight but a few.

In this natural habitat they became entirely dependent on pastures to sustain their nutrient requirements. Considering their numbers at the time they adapted quite well to these conditions consuming high fibrous food over prolonged periods of time. By definition we could say that they were continuing grazers.

No longer having the protection of the forests they became prey to many a predator, including man, and had to run for their lives often, hence the superb athletic qualities they possess today. Their protection mechanism was one of “fright and flight”. Due to this they are naturally nervous animals and are easily spooked by any strange object or quick movement.

Human interference started around 4000 BC and by 3000 BC domestication was wide spread. Today we push these animals to limits they can no longer sustain without supplementary feed sources. To apply the latter responsibly it is vital to understand the abilities and limitations of their gastro intestinal tract (GTI) as it developed through the evolution process.

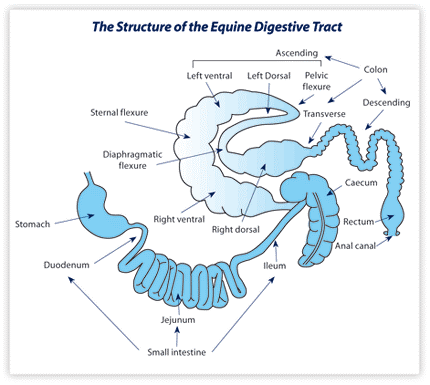

The GIT or digestive system developed a very specific mode of operation with certain limitations that should be considered when designing feeds or feeding programs. The GIT, as depicted in the Figure below has two very distinctive sections, the fore gut and the hind gut.

The fore gut is a normal single stomach (much like that of the human) where digestion is facilitated by enzymatic action in an acidic environment with a pH of about two. It consists of the oesophagus, stomach and small intestine with the latter entering into the caecum, where the hind gut starts. The fore gut comprises 38% of the total volume of the GIT. Food passage is very rapid and ingesta reach the hind gut within 1.5 hours from eating a meal.

The stomach itself has a capacity of 8 – 15 litres and represents 9% of the GIT volume. It is here where most (52 -58%) of the protein and soluble carbohydrates, such as sugars and starches are digested and then absorbed in the small intestine.

The hind gut makes up 62% of the total volume of the GIT and consists of the caecum, large colon, small colon and rectum. The caecum, also known as the “blind gut” makes up 16% of the volume and has a capacity of 28-36 litres. The large colon makes up 38% of the volume with a capacity of 86 litres whilst the small colon and rectum make up the balance.

Food passage through the hind gut is slow (approximately 18-24 hours depending on the kind of ingesta). Digestion is by bacterial fermentation that is optimal in a neutral environment at a pH of seven over a prolonged period of time. It is here where the fibrous portion of the diet is digested, slowly releasing volatile fatty acids (VFA) through the fermentation process which is absorb by the animal as an energy source.

Keeping the bacterial population intact is vital to the animal’s health and the sound functioning of the hind gut. In fact the prime objective should be to feed and manage the feeding program in such a way that an optimal environment is created for the microbial population in the hind gut, because it is the latter that actually feeds the animal. These populations are very sensitive to any sudden changes in diet and/or pH.

The hind gut is capable of digesting starches and sugars but does so by fermentation unlike the fore gut where it is done by enzymes. The fermentation of starches and sugars is a much faster process than that of fibrous materials like roughage. Consequently the formation of gas and lactic acid is prolific and can cause a number of digestive disorders. The formation of excessive gas can cause colic whilst excessive lactic acid causes the pH to drop killing the desired bacteria leading to the proliferation of undesired bacteria. The excessive formation of VFA, more than the animal can absorb, may also lead to the onset of laminitis.

Considering this it is vital to avoid the over flow of starches and sugars into the hind gut. In their natural habitat horses did not have to contend with these problems. However, since man intervened and exposed them to activities that require a higher plain of nutrition than can be derived from fibrous material only, we started feeding them concentrates that contains starches and sugars and we should do this responsibly. We know that the passage of food through the fore gut, where starches and sugars are digested effectively, is rapid. It stands to reason that any excessive intake of concentrates that contains large amounts of starches and sugars will cause an over flow into the hind gut.

So to keep your horse healthy and both you and your horse happy here are a couple of golden rules that should never be broken.

Maybe all of this will change in the next 10 million years but you can rest assured that it will not happen in your and my life time. So let’s manage what we have with the necessary responsibility making sure that both horses and owners are happy chappies.

Until next time, happy racing, riding and breeding from all at Equi-Feeds - the leaders in equine nutrition though quality and consistency combined with technology and innovation.

It all started about 55 million years ago when a small “dog like” animal called Eohippus (dawn horse) emerged from the forests of the North American continent to roam on the grass planes of the world. Here they evolved to the modern horse, Equus caballus, a majestic animal of high intelligence and a superb athlete. The evolution process was a complex one going through many phases but for our purpose it will suffice to highlight but a few.

In this natural habitat they became entirely dependent on pastures to sustain their nutrient requirements. Considering their numbers at the time they adapted quite well to these conditions consuming high fibrous food over prolonged periods of time. By definition we could say that they were continuing grazers.

No longer having the protection of the forests they became prey to many a predator, including man, and had to run for their lives often, hence the superb athletic qualities they possess today. Their protection mechanism was one of “fright and flight”. Due to this they are naturally nervous animals and are easily spooked by any strange object or quick movement.

Human interference started around 4000 BC and by 3000 BC domestication was wide spread. Today we push these animals to limits they can no longer sustain without supplementary feed sources. To apply the latter responsibly it is vital to understand the abilities and limitations of their gastro intestinal tract (GTI) as it developed through the evolution process.

The GIT or digestive system developed a very specific mode of operation with certain limitations that should be considered when designing feeds or feeding programs. The GIT, as depicted in the Figure below has two very distinctive sections, the fore gut and the hind gut.

The fore gut is a normal single stomach (much like that of the human) where digestion is facilitated by enzymatic action in an acidic environment with a pH of about two. It consists of the oesophagus, stomach and small intestine with the latter entering into the caecum, where the hind gut starts. The fore gut comprises 38% of the total volume of the GIT. Food passage is very rapid and ingesta reach the hind gut within 1.5 hours from eating a meal.

The stomach itself has a capacity of 8 – 15 litres and represents 9% of the GIT volume. It is here where most (52 -58%) of the protein and soluble carbohydrates, such as sugars and starches are digested and then absorbed in the small intestine.

The hind gut makes up 62% of the total volume of the GIT and consists of the caecum, large colon, small colon and rectum. The caecum, also known as the “blind gut” makes up 16% of the volume and has a capacity of 28-36 litres. The large colon makes up 38% of the volume with a capacity of 86 litres whilst the small colon and rectum make up the balance.

Food passage through the hind gut is slow (approximately 18-24 hours depending on the kind of ingesta). Digestion is by bacterial fermentation that is optimal in a neutral environment at a pH of seven over a prolonged period of time. It is here where the fibrous portion of the diet is digested, slowly releasing volatile fatty acids (VFA) through the fermentation process which is absorb by the animal as an energy source.

Keeping the bacterial population intact is vital to the animal’s health and the sound functioning of the hind gut. In fact the prime objective should be to feed and manage the feeding program in such a way that an optimal environment is created for the microbial population in the hind gut, because it is the latter that actually feeds the animal. These populations are very sensitive to any sudden changes in diet and/or pH.

The hind gut is capable of digesting starches and sugars but does so by fermentation unlike the fore gut where it is done by enzymes. The fermentation of starches and sugars is a much faster process than that of fibrous materials like roughage. Consequently the formation of gas and lactic acid is prolific and can cause a number of digestive disorders. The formation of excessive gas can cause colic whilst excessive lactic acid causes the pH to drop killing the desired bacteria leading to the proliferation of undesired bacteria. The excessive formation of VFA, more than the animal can absorb, may also lead to the onset of laminitis.

Considering this it is vital to avoid the over flow of starches and sugars into the hind gut. In their natural habitat horses did not have to contend with these problems. However, since man intervened and exposed them to activities that require a higher plain of nutrition than can be derived from fibrous material only, we started feeding them concentrates that contains starches and sugars and we should do this responsibly. We know that the passage of food through the fore gut, where starches and sugars are digested effectively, is rapid. It stands to reason that any excessive intake of concentrates that contains large amounts of starches and sugars will cause an over flow into the hind gut.

So to keep your horse healthy and both you and your horse happy here are a couple of golden rules that should never be broken.

- Depending on activity and weather conditions your horse will consume between 5 and 8 litre water per 100 kg body weight per day. In the case of lactating mares this increase to 12 litre. Clean water of good quality should always be available. Assessing quality is easy; if you won’t drink it don’t expect your horse to drink it.

- Always feed your horse good quality roughage ad lib (it should be available at all times). The pain of problems caused by bad quality roughage lasts much longer than the pain of paying for good quality roughage.

- Feed concentrates in small quantities several times per day (preferably not more than 2 kg per feeding); this will ensure that the starch intake is within acceptable limits (approximately 600 to 800 grams).

- Ensure that the concentrate portion of the daily feeding program never exceeds 50% of the total daily intake (at least 50% of the total daily intake should be good quality roughage)

- Don’t feed bits and pieces of additional supplements unless you are addressing a specific problem or requirement (most commercial concentrates are designed as fully balanced rations and should supply all the nutrients your animal needs)

- Determine the weight of the concentrate you feed at regular intervals to ensure that you are still within acceptable parameters.

Maybe all of this will change in the next 10 million years but you can rest assured that it will not happen in your and my life time. So let’s manage what we have with the necessary responsibility making sure that both horses and owners are happy chappies.

Until next time, happy racing, riding and breeding from all at Equi-Feeds - the leaders in equine nutrition though quality and consistency combined with technology and innovation.